Citizens and Nationals

Merritt Tierce

Ernesto has been asking me to marry him for the past five years. Sometimes six months will pass without a proposal but he has not yet given up. I tell him we could never pull it off, that INS is too tough, but to be honest I wonder if I would take the risk if he just offered me more money. Five thousand dollars I give you, he says, opening all the fingers of his hand for emphasis.

I can tell he doesn't believe me when I explain how hard it would be to convince the authorities that we weren't doing exactly the thing we'd be doing. Ernesto speaks fluent restaurant English but I know if I elaborate by telling him I read about a New Jersey couple that had been married for fifteen years, had two little kids and a mortgage—the woman was 2nd generation Mexican American and the man was Ukrainian, and the man was deported because INS was convinced their life together was fraudulent—I know I could not get even this much across to Ernesto, I know he would look at me the way he does when he doesn't understand what I'm saying and doesn't want me to know. Forget trying to explain further, that the journalist had clearly been certain there was nothing false about the union, in spite of the fact that the man Marko could not say where they went on their first date and the woman Liliana, when questioned by the investigators, said her husband had two brothers after he'd reported in a separate room only one.1 If we could discuss this a facility of language and comprehension would be at work that might make possible a sham marriage but would also mean Ernesto could wait tables instead of bussing them, and easily pay me twice as much for this favor. I would think our chances as good as his English, since having been seen with a book reviewer so often over the same five years could count against me if I married a man who didn't understand the word 'sham.'

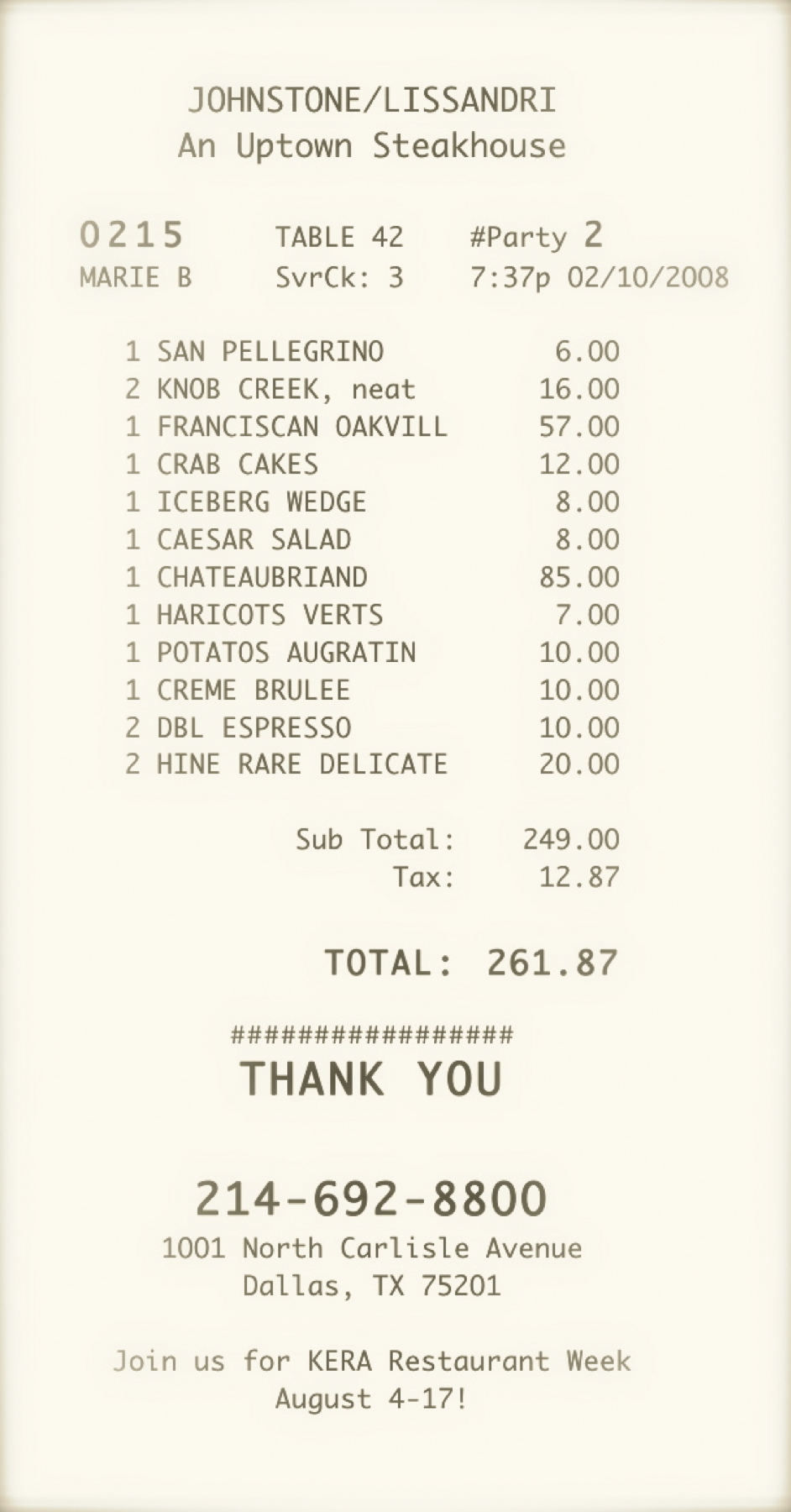

Garrison said once that his name was from the Old English, that he was a walled town, and he was. You couldn't call him Gary. He would come into the bar at Johnstone/Lissandri, the fine-dining Dallas steakhouse where I've waited tables for six years, near the end of my shift and drink a Knob Creek neat while he read his latest assignment. I would offer to buy him a couple of appetizers or he would ask me could I get him some of those lamb ribs Chef made. The Mexican, Guatemalan, Salvadoran, and Venezuelan line cooks and bussers and expos did not respect him because they knew I paid for his food, but they would have invented an excuse to disrespect him anyway because he is black. Why you don't like Mexicans, Ernesto asks me, with scorn that bows up, starts out defensive but flips over somewhere in the middle to become plaintive. Eh? Why, Maria. Most of Ernesto's questions are statements, their dissatisfying answers foregone.

I've kept a spreadsheet of all the men I've had intercourse with, including information about not only the men themselves but the date, place, and circumstance. Ruben César Rivera-Perez had puppy eyes and was the pizza chef at an Italian restaurant where I worked before J/L. I gave him a key to my apartment after we did it the first time and I asked for it back a month later but in between we'd spent every night in my bed, fucking and cuddling. We took a bath together, which is something I never have done with Garrison in five years of him. I went with César to his aunt's birthday party in Mesquite and his four-year-old cousin told me I was bonita. I've never met Garrison's family.

Many of the Spanish speakers in my restaurant have asked me at different times over the years where I learned Spanish even though I am not fluent. It is that my pronunciation implies I know the language better than I do. Tenía un novio de San Luis Potosí, I say. This explains all. I don't mention that there were two of them in succession, two men from San Luis Potosí, I don't mention that I cannot remember without checking the spreadsheet which of them was October 20042 and which November,3 that I cannot remember which one I left for the other. Enrique was much older than César and insisted I call him Henry, he had a gold front tooth and three children and a wife so he would go home afterward. I remember the one I quit was pissed and I'd have to look at his back at work every day after that. But the important thing is I can use the word novio when I say how I learned Spanish, whereas whenever Ernesto comes to tell me my novio is in the bar I correct him. I have been correcting him for five years. He does not keep using that word because he has forgotten and I do not keep correcting him because I care that he gets it right. It is just a ritual. He is really saying Don't forget you've chosen a man who withholds all that from you and I am really saying Don't worry, I won't.

When Ernesto pitches it he always mentions that he is a clean-living prospect for a fake husband. I no drink, he says, I no smoke. He has pale skin and thick thick black hair that is longer than mine but for service he keeps it gelled back. When he talks to me he adjusts his glasses professorially. He says he cooks. Garrison cooks for me almost every night when I get out of work. He does not allow me to stand in the kitchen and talk to him. If I try to enter the kitchen for another reason, to wash my hands or get a glass of water, he says What do you need. If I take a glass from the cabinet he says Why don't you ever wash one instead, or he says Go sit down.

The kitchen contains these moments, contains the tight way he speaks to me, the perturbation I cannot help but jostle no matter what I do around him, like the stainless steel martini glasses I have to carry at J/L. The martini costs $21 so it must be filled to the brim but it is a Y-shaped glass with a straw-slender stem so it is impossible to carry without spilling some. I have learned to walk with my buttocks clenched, to roll my feet, to grip the edge of the tray with one hand and press the base of the glass to the tray with my other, I have learned how to make my body stiff if someone bumps me so that the current is stifled, does not pass through me to the tray. Still, only a ballerina or an acrobat could do this perfectly. I am just a waiter who wants to be a writer. For no good reason I am in love with a man who is impossibly full of other things.

Ernesto asked me for my email address years ago. The bussers and line cooks all have morning jobs in different restaurants and they are all undocumented and share rides or ride bicycles long distances on dangerous Dallas roads to get to work, but they have email and iPhones and they're on Facebook. The dishwasher stands in bilge water so deep Chef bought him some knee-length waders, but he props his iPhone on a shelf of the Hobart out of reach of the nozzle's spray and watches porn on it. He throws cement for eight hours during the day and gets to J/L at 6:30. He likes to give me a hug. Mareeeeeeeya, he says, Te ahhhhhhhhmo. His body is like cement, from throwing cement. He is five feet tall and I am one of the few servers he has not asked for money. He shows you a picture of his wife and seven children in Toluca and tells you all their names and asks for twenty bucks. I don't know why he hasn't asked me.

The first two years I knew Garrison I tried to compensate for the fact that I was a waiter by paying for things if we went out. I believe this was not simply stupid but immoral, as I have two young children and he does not. I bought him. A $300 dinner at Lola, a $300 dinner at Nobu, a $1000 weekend at the W, plus our regular tabs once or twice a week after I got out of work. Brunch or dinner on Sundays and a new pair of running shoes. I paid when he brought his old college roommate Sanjay into J/L for a good steak, $2504 off the top of what I made that night. But these were all my ideas, my efforts to participate correctly with someone who claimed to have been chronically mistreated and shafted by women. I think the W is cheesy, I don't know what I was thinking. I'm not an Uptown girl. I could have been fine forever on the couch with a movie and a beer and a pizza.

Sanjay was visiting from somewhere in Europe—Sweden or Switzerland. I came over to Garrison's apartment after I waited on him and Sanjay, Sanjay was asleep in the front room at the end of a long hallway. In the kitchen at the other end I sat in a chair quietly while Garrison made me some fish tacos. I had a glass of water I sipped from and kept under the chair while I looked at his Bookforum. Because the table was covered with his books and papers he didn't want me to sit there, so I was in a dark space off the kitchen next to the washer-dryer. I was so hungry. I had not eaten in twelve hours and was alternately shaking with hunger and falling asleep. He gave me the plate of tacos and a fork. He hadn't said anything to me since I arrived but Have a seat. I took a bite of the first taco and it was so good I shifted my body in the chair, I leaned back with my eyes closed to show how good, how excellent it was to have food, and my foot knocked over the water glass under the chair. It made a tremendous clattering on the ceramic tile. Water appeared all around me. I leaned forward so quickly to pick up the bouncing glass that my fork fell onto the floor, the same clattering refrain in a different key. Jesus Fucking Christ, he hissed. What's wrong with you? He threw a roll of paper towels at me.

Yet this is the kitchen that also contains the moment when we were hot, it was summer, I was skinny as a little tree-climbing child. He took off his shirt in that kitchen and wiped his sweating head. He opened a beer, he took a sip, he held it to the side of his head, his neck, he set it down, he kissed me, he took off my shirt, he kissed me, I put my arms around him, he dropped his gym shorts, he lifted my skirt, lifted me onto his hips, he leaned forward and pushed into me like everything you've ever wanted from a man. He held me, he held my whole body and came so fast.

I have never gone home with Ernesto. The sole busser on the spreadsheet is Teo Plaza, from when I was new at J/L and before I met Garrison and quit using. Teo and I would do coke in the employee restroom during the shift, and sometimes he would bring a twenty-bag to the café where I still worked in the mornings if it was slow and I called him. One night I let him come over to my apartment, we did it on the floor in my living room and it was fast but not in a good way. I didn't want him to stay. He was a maniac in the restaurant, watching him reset tables was like watching a reversal of that trick where you rip the tablecloth from under the place settings. He was tall and thin and belonged to the group of willing bussers who had the right urgency, the quickness. The unwilling bussers looked bored or tired and stood up too straight. There is an angle of intention, it's slight but communicates everything. One night Teo was helping another busser move a heavy bitch of a table and they were going too fast, he lost his grip for a second and the metal pedestal sliced off his left big toe except for a meaningless isthmus of skin on the side. He had to go back to Guatemala and I never saw him again.

Ernesto assures me he is not married to the mother of his children, who are almost grown. He has been in this country for a long time. I think it shouldn't matter if he is married already or not, if we are plotting to break the law anyway, but I appreciate his interest in addressing all possible objections. Then I think maybe he doesn't consider the marriage an outright crime. Maybe he thinks of it as a marriage of convenience, one reason among many to marry someone. This may in fact be a higher order of thinking about marriage than I am used to. What is the difference between Ernesto who wants to marry me for a green card and the women who come into this restaurant, hoping to marry money?

When he tells me he has paid his taxes here for twenty years, I think he should be able to go somewhere and trade that honesty for citizenship before he has to pretend to be in love with someone. But I could do a lot with five thousand dollars, and I tell Garrison that Ernesto keeps proposing. He says I should accept. He says it the way the Mexicans ask me why I don't like them, the same mocking tone. When I say What do you mean, I should accept? he shrugs and Sounds like a good deal to me, he says. Sometimes when Garrison posts up at the bar at J/L Ernesto will stand a few feet away from him, facing out toward the entrance to the dining room, and make vulgar expressions of some kind as I walk toward Garrison. Like he will lick his lips as I walk past and say I hungry, Mami, I hungry. Come on, Maria, why you make me wait. I hungry.

Garrison calls me Mami when he wants it or while we're doing it. This is not because he speaks Spanish because he doesn't or because I have children even though I do, it is because of Junot Diaz and stories like Alma5 and The Sun, the Moon, the Stars.6 My spreadsheet says of him that he was 33 and I was 26 the day we met, that he is Congolese American, that the first thing he said to me was Excuse me, is that poetry you're reading? There is a column, heading Number of Times, that reports 1 for most of the 61 names on the list, and 672 for Garrison. There is no column in which I can indicate how satisfied I am with the encounter/s, because that would require creating an algorithm that could cross my deep sexual delight with perpetual emotional disappointment, and I have never yet figured out the proper coefficient of correlation.

Since I met him I have edited 37 reviews he's written but he does not invite me to hang out with his friends, who are Dallas writers and artists. He tells me of a drink he had with a local architect, a young woman my age. I think this is what he wants—alliance with someone tagged. Someone whose accomplishments can reside and glitter in a single word. He can't introduce me: when he does, he says I am a writer. You've already gotten so much done, the architect said to him. So the idea that if/when I lose him I will lose something I did not want is a harness, I check and double-check its buckles and fibers and it seems sound. Yet Elizabeth Hardwick dies and frays it:

[Crazy abusive Robert] Lowell went back to [his second wife] Ms. Hardwick in the spring of 1977, after the breakup of his marriage to [his third wife, the British novelist and heiress] Lady Caroline, but he died of a heart attack on Sept. 12…Ms. Hardwick said she had no regrets about the marriage. “The breakdowns were not the whole story,” she said. “I feel lucky to have had the time; everything I know I learned from him.” She added, “I very much feel it was the best thing that ever happened to me.” 7

So far I have published only one story, but it won Pontchartrain Review's $2,000 emerging writer prize, and then a Pushcart. In a way I have leapfrogged over Garrison with this, because he also wants to be a fiction writer, not a book reviewer. The day that I like Pushcart Press on Facebook, Ernesto does too. You and Ernesto Elizondo like Pushcart Press.

When Ernesto and I work together it is a beautiful athletic event. He is more backwaiter than busser and I can take twice as many tables if he is assigned to me, so I give him a lot of money. I don't need to tell him what to do, it's just a series of eye contacts made across the dining room, a few hand signals we have worked out over the years that result in the instant appearance of bread and butter or disappearance of finished salad plates. Because I came up in turn-and-burn cafés I don't like any slack in my service even if the people usually sit at the table for two or three hours, and Ernesto gripes at me for how hard I push but all I say is Come on Ernesto we gotta make that jack, and I keep moving.

He sent me an email once, subject: i love. In the message body all it said was, again, i love.

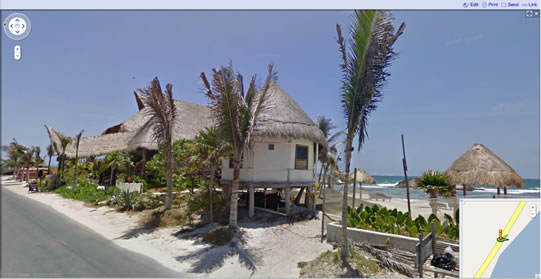

The terms of the marriage deal also include the use of Ernesto's beach house8 on the Yucatan peninsula, in Tulum. He knows I write and suggests I go there to get away from J/L and think. He tells me I can stay in this house whenever I want, that it will be good for my kids, he describes the kind of sand they have there and asks me if I like to swim. He himself cannot go back.

—

I have used Ernesto's interest in me one time and it was a night I came to work straight from Garrison's, which I often did, he thought it gave me good luck to have a vigorous session in the afternoon before I went into J/L. I had encouraged this idea at the beginning of our knowing each other, because when I got out of work he would ask me how much money I'd made. If I'd had a good night I would say It must have been what you did to me earlier. He liked that and it gave him a way to ask me for sex as if he were doing me a favor, as well as a tenuous license to my earnings. That particular afternoon he had at last received the galleys for a collection of his reviews and essays, which was to be his first book. We celebrated, he had killed most of the remaining third of the bottle of Laphroaig I'd given him for Christmas and poured me the last finger before reaching for my belt buckle. Papi adores you, he said into my neck as he thrust, There, there, there, he said, Take that and have a good shift. Mami's gonna make all the money tonight.

He had never said anything like Papi adores you to me and I knew it was only because he was afloat on a glowing peaty wave. Third person and all I let it make me feel drunk too, until I picked up the galleys while he finished ironing my shirt, another aberrant gesture I judged to have arisen out of scotch- or publication-induced largesse.

I flipped to the back, to the acknowledgments, because in the manuscript he'd sent to the publisher, which I had line-edited and read at least three times, he had said In Dallas I am especially grateful for the love and friendship of Marie Broyard and I liked reading that part over and over. The word love had never been spoken by either of us and I knew he didn't want it to be, but he had put it on the page. Here's your shirt, he said, as I read in the galleys In Dallas I am especially grateful for the friendship of Marie Broyard.9 Thanks, I said, but why did you take out my 'love'? What do you mean? he said. Come on, I said, don't play dumb. I'm sorry, he said. I threw the galleys at him, they flew across the room hard and heavy, flapping. Fuck you, Papi, I said, Fuck you for thinking I wouldn't notice that shit.

I was rattled by this and as I drove to work I couldn't get the dimple in my tie right even though that was something my hands usually did without any help from my brain, without a mirror. He called me but I didn't answer. I got to the restaurant four minutes late and set my tools down on a stack of napkins in the back, to retie my tie once more. I picked up everything except my waiter book, which I had had since my first day at J/L. I realized it a few minutes later but when I went back to the stack of napkins it wasn't there, and at the same time the hostess came looking for me because she had seated my first table. I greeted them without my book and got Ernesto started on their water and a couple of iced teas and I rang up their cocktails and then went looking for my waiter book in earnest.

It was a check presenter, so it looked like every other check presenter stacked near the POS terminals. What made me anxious to find it was that inside it was a drawing my son made for me when he was 4, right before I started at J/L. The drawing showed him and his sister as smiling shorties under a tree. There was a house with blue smoke coming out of the chimney even though we had never lived in a proper house. A giant sun took up half the little page. I had laminated it with clear packing tape. Every time I had ever taken an order at J/L, approximately four times a night times six nights a week times fifty-one weeks a year times six years, I had seen that picture when I opened my waiter book.

Victor, I say to the dishwasher, who says ¿Sí, mi amor, qué quieres? ¿Has visto mi libro? I ask, making an open-close book motion with my hands, bound at the pinkies. I explain about the drawing. Sí, sí, Mariquita, he says, affirming its importance to me, but he hasn't seen it. I ask everyone. No one has seen it. The martinis are waiting at the bar and by now are not as cold as they need to be, the ice shards that should float on their surfaces have melted. Ernesto comes to tell me that someone at the table wants to order wine. Ok, ok, I'm coming, I say, Ernesto can you please find my book. I will let you have what you want if you will just find my book. It has a drawing in it. I know, I know, he says, I see it. I find.I wait on the table. I get another table. I do not have time to do anything but take care of these people but I feel as though a balloon is floating away from me and nothing is going to make it stop. I am talking about the steaks we serve and the fish feature, the long version of my spiel takes six and a half minutes and the short version takes three minutes. I don't even know which one I'm doing, my mouth can do this on its own. I am thinking about that drawing and how much I don't want to lose it. There is an owl hole in the tree. All drawn trees have owl holes and all drawn chimneys have smoke, and all drawn children are happy.

I am willing to fuck Ernesto for this if he comes through, or let him eat my pussy or whatever it is he wants. I am doing things for the table that he normally does, while he looks for my book. I have refilled the iced tea glasses and set out the mise-en-place for appetizers and decanted two bottles of wine and I am taking the dinner order, bending down to hear what temperature this man wants his ribeye when behind his shoulder Ernesto comes out of the dishroom holding my book up in the air so I will see it.

Gravy. The rest of the night is oiled by the taste of scotch I had before work which I can now submit to because of the recovery of the book. I stare at the drawing every time I have two seconds to open my book, I have not really looked at it in a long time. My son got a stunt bike for his 10th birthday and fractured his thumb when he landed wrong at the half-pipe near our apartment in Oak Cliff but he is proud of this and of the scrapes all over his legs. He weighs one hundred pounds, which he announced to Garrison the last time Garrison came over. My work in this restaurant has made a bridge for us to walk over, six years of provisions stretching from this baby-drawn drawing to now, my work has fed him into these one hundred pounds and bought him a fractured thumb he thinks makes him tough and has put in our living room a double bass his younger sister is learning to play. I bought it off craigslist, a used ¾ size. (Mark Wahlberg came in with his posse one night when the Mavs made the playoffs and the Lakers were in town. I didn't do anything special but he tipped me the exact amount of the bill, which was $1,432.56. There were only five of them but they drank Cristal and Louis XIII and each one of them had a lobster with his steak. She said Thank you Mama, thank you so much, when we went to pick up the bass, and I said Thank Marky Mark, lamb.) You should see her tiny peachy face, such solemn concentration over the fingerboard.

Victor asks me if I found the book when I go back there and I say Yes! Nesto found it! and I show him the drawing. ¿Cómo están tus niños? he asks. They're good, I say, they're very big. I ask him how his are. He pulls out the picture and tells me all their names.

As I am running my cashout after the last guests have gone Ernesto puts his hand on my neck and says into my ear I hungry. I know, I say to him. Tonight? he says. Ok, I say, dreading it, but I know I can do it. Before I met Garrison I had so much bad sex, and I know how to make it end quickly. It's that angle of intention, it works in hips too. Just lean into it for a couple beats and when he feels that from you it's over. That's all he wanted anyway. Ernesto has a nice solid body, in addition to restaurant English he knows a lot of gym English and has told me about his workout routine. 24-Hour Fitness in the middle of the night after J/L, arms on Monday, Wednesday, and Friday, legs the other days, circuit cardio, domingo descansa. But in the dark alone with a man it is language I respond to so this attempt to focus on Ernesto's appealing physique doesn't pass, being only lamehearted to begin with.I don't want Ernesto to know where I live but I don't want to know where he lives either, and the kids are with their dad so I tell Ernesto he can come over. I usually call Garrison when I get out of work but when I don't tonight he will think it is because of the love incident, which I forgot about until now because losing the book was more important than losing the love. It's possible that Garrison could come by my place and see a strange car out front. Even if he doesn't he always asks me about time that is unaccounted for.

Ernesto is waiting for me in the parking lot as I shut down the restaurant. Lately he has taken up a new tactic regarding the proposal, which is announcing that if only I had agreed to marry him five years ago, or even three years ago, or just twenty months ago, it could all be over now. Twenty months, I free, he says, shaking his head. I am plugging in the bug blacklights on my way out the back door when Victor comes past me dragging the thirty-gallon trashcan to the dock so he can go home too. He pauses. Maria-Bonita, he says, and tells me how his kids need a lot of things for school and asks if he can borrow forty dollars. He knows I make good money. They all know who makes what but I am mildly surprised at his shrewdness, to ask me not within the moment when I got back the book but some hours later, though still on the same night, as if he has always meant to ask me and keeps forgetting because it's not that important. But I know there is never a time when he does not need the forty dollars. I know the only food he eats is what the bussers and servers bring him, the leftover sides and the overcooked steaks and the I-didn't-like-its. I know he takes home bread and butter and I know Chef gives him a gallon or two of soup when it's about to turn. I do have forty dollars in my pocket but I was going to give it to Ernesto. I decide Ernesto will have enough from me tonight so I give Victor the money. He embraces me with damp arms. Mucheeeeeesimas gracias Mari, he says.

De nada, Victor, de nada, nos vemos, I say to him but I am thinking about what I will say to Garrison when he asks me tomorrow or the next day where I was tonight, what I did after work. He will yawn as though it doesn't matter to him, as though he's making absentminded small talk, as though he's no more than half interested in my reply. I will say I don't understand why after all these years no one in his life knows that he loves me, that he feeds me, that he sleeps with me almost every night. I will fail to explain why it matters and he will ask why we have to have the same friends. I don't like lying to him so I will tell the story of how I went home with that busser who kept asking me to marry him and Garrison will say Well there you go, number 62! because I made the mistake of showing him the spreadsheet once.

And when summer comes he will take his other woman, who is also Congolese American and lives in Ohio and knows his mother, to Tulum for Sanjay's destination wedding. He'll be the best man and she'll be the one everyone sees with him. It's just a coincidence—Tulum—but when I think about them on the sand there I will say to Ernesto ten and then yes. Yet as I leave the restaurant tonight all I want is to go where I always go. Let him make me some tacos and then make it up to me.

¿Me sigues? I say to Ernesto when I see him leaning on my car in the parking lot. He does not like it when I speak to him in Spanish.

-----

1 See also “Immigration, a Love Story,” by Mireya Navarro, New York Times 12 November 2006: 'Immigration Services officials say they are not out to impede love or immigration.' ↑

2 Via http://www.me.com/idisk/thelist.xls: Enrique. ↑

5 While a review of “Alma” reveals no instance of Mami, this must be how pópola entered our bedroom vernacular. Junot Diaz, “Alma,” The New Yorker 24 Dec. 2007. ↑

6 Cf. Even Magda wasn't too hot on the rapprochement at first, but I had the momentum of the past on my side. When she asked me, “Why don't you leave me alone?” I told her the truth: “It's because I love you, mami.” Junot Diaz, “The Sun, the Moon, the Stars,” The New Yorker 2 Feb. 1998. ↑

7 Christopher Lehmann-Haupt, “Elizabeth Hardwick, Critic, Novelist and Restless Woman of Letters, Dies at 91,” New York Times 5 Dec. 2007. ↑

9 Kalubi, Garrison Mulombu. Notes of an Immigrant Son: Reviews and Essays on Diasporic Intellectual Thought. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2009, p. 187. ↑

Merritt Tierce is a graduate of the Iowa Writers' Workshop. Her work has appeared or is forthcoming in New Stories from the South, Southwest Review, PANK, Cutbank, and Reunion: The Dallas Review. She is the director of the Texas Equal Access Fund and lives in Dallas with her children. You can contact her at merritt dot tierce (at) gmail dot com.